Several Legislative Changes of the Last Decade That Weakened the Georgian Media

Introduction

Georgia’s first peaceful transition of power in 2012 brought an opportunity to further broaden the country’s democratic transformation process. This progress, together with some other fields, should have been reflected on a degree of media freedom which is one of the most important preconditions for consolidation of democracy. In the first years of the Georgian Dream’s rule there was a clear-cut positive trend in terms of media freedom, although this trend was soon halted, particularly after the Georgian Dream won second straight term in the Parliament (with a constitutional majority). In the third term of the Georgian Dream, however, media freedom in Georgia has been deteriorating every year. This is clearly illustrated by the media freedom indices published by the internationally recognized organizations, where Georgia’s indicators worsen and the country loses positions vis-à-vis other countries. Of numerous factors that undermine the degree of media freedom, legislative changes have their important place, as they have weakened financial sustainability of media outlets as well as their degree of independence. This document offers an overview of those legislative regulations and their potential or already established negative consequences.

Legislative Changes that Weakened the Georgian Media

On 31 October 2014, the Parliament of Georgia enacted amendments in regulating social advertisements. As a result, broadcasters were allowed to sell their air time to administrative bodies to place social advertisements only after they have filled free-of-charge airtime legally allotted for social advertisement – at least 90 seconds for each three-hour period. In other words, before changing the law, broadcasters were allowed to take money from state administrative bodies to place social advertisements even if the abovementioned 90 seconds were not fully used. After the changes, however, they have to allot at least 90 seconds for free-of-charge social advertisements because only in this case will they be allowed to place paid social ads.

Generally, it is a matter of separate discussion how relevant it is to obligate a private media organization to broadcast free-of-charge social advertisements. In regard to amendments enacted in 2014, they are important not only from financial point of view (affecting advertising revenues), but in terms of independence as well. In particular, a new passage was added to the Law of Georgia On Advertising that “if an administrative body and a broadcaster fail to reach an agreement about whether the material provided to the broadcaster by the administrative body is a social advertisement and/or whether it contains information which is important for the public, the Commission shall settle the dispute within 10 days after one of the parties files an application with the Commission as determined by the General Administrative Code of Georgia”.

As a result of this passage, Georgian National Communications Commission (GNCC) was allowed to participate in discussion over content of product broadcast on media and most importantly to make a relevant decision. Naturally, this increased the role of a regulator in a field that could be considered as belonging to the broadcasters’ scope of self-regulation. This novelty was also problematic because generally it is hard to have precise and comprehensive definition of a social advertisement, although the idea of social advertisement is more or less clarified in the amendments adopted on 31 October 2014.

IREX media sustainability index 2015 report also offers reflection on regulating social advertisement in such manner. In particular, it underlines concerns of the Georgian media and NGOs that with the changes, GNCC was essentially granted excessive power over broadcasters whereas the definition of social advertising still remains rather vague.

Of note is that the GNCC made use of this right, granted to it in 2014, multiple times vis-à-vis different broadcasters. This is beyond the scope of this paper to ascertain whether or not a certain disputable issue did fit with the definition of social advertisement. Here, most important thing is that there are numerous instances of enforcement this regulation and interference in broadcasters’ freedom.

In 2015, amendments were enacted in the Law on Broadcasting which determined precise intervals of advertisement or teleshopping placements. As a result of these changes, advertising time became regulated and therefore limited. The government’s position was that adoption of those changes was a requirement of the European Union’s directive, although as it turned it, the relevant directive does not require such tight regulations which were envisaged by the initiated amendments.

In particular, new amendments banned interruption of official state event, speeches of highest public officials and religious ceremonies by advertisements. It was also forbidden to interrupt those public/political and religious programs, pre-election debates or documentaries whose duration is less than 15 minutes. According to the Section 2 of Article 20 of the European Union’s Directive, television advertising should not be inserted during religious ceremonies only and it does not envisage further restrictions listed above.

In addition, it was established that on a broadcaster's channel (except for specialized advertising channels and/or teleshopping channels), commercial advertisements and/or teleshopping spots shall be placed in the advertisement breaks so that their volume during the broadcasting hour does not exceed 20%. Therefore, time allotted for advertisements was limited for the broadcasters. Of note in this context is that 12 minute per hour restriction does not apply to statements of the broadcaster that are made with regard to its own and/or independent programs (so called announcements). European Union’s Directive does indeed envisage such restriction, although implementation of this norm of the Directive could have been carried out gradually and reach 12-minute limit over the course of five years. Furthermore, Article 26 of the same Directive reads that Member States may lay down conditions other than those laid down in Article 23 if the entities concerned are broadcasters operating in one country only and different approach does not contradict the European Union’s legislation.

Of note is that as a result of the amendments enacted in the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting in December 2022 the abovementioned interval was changed as follows: “On a broadcaster's channel except for specialized advertising channels and/or teleshopping channels, commercial advertisements and/or teleshopping spots shall be placed in the advertisement breaks so that their volume from 06:00 to 18:00 does not exceed 20% of that period and from 18:00 to 24:00 does not exceed 20% of that period”. With this amendment, period from 12:00 AM to 06:00 AM remains outside the scope of stringent restriction which means that regulation was relaxed to a certain extent. Although, it is hard to say how lifting restrictions on advertisements in late night hours will affect the broadcasters’ income.

Yet another noteworthy restriction in the 2015 amendments’ package was about programs partially or fully financed by a sponsor. In particular, indication to a sponsor in a program partially or fully financed by the sponsor and in the broadcaster's statement regarding its own and/or independent programmes shall be concise and shall not exceed four minutes within a broadcasting hour. European Union’s Directive did not at all require imposition of such restriction.

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, in its 2015 resolution, assessed these changes as aimed at curbing the financial independence of private and thus potentially influencing their editorial independence.

In February 2018, amendments to the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting which removed most of restrictions on commercial advertisements and sponsorship, went into effect. It was allowed to place commercial advertisement at public broadcasters except for the so-called prime time (19:00 to 24:00) and week-ends. According to the changes, “sponsored and commercial advertisements may be placed in these channels only within the framework of sports programs, international festivals and contests, at the beginning, during a natural break or at the end of a competition program. In this case, the duration of a commercial advertisement shall not exceed 60 minutes within a 24-hour period, 12 minutes per hour (20%) and in all other cases duration of commercial advertisement shall not exceed 3 minutes (5%) per hour”.

Consequently, Georgia’s Public Broadcaster which is already financed from the state budget and its funding grows proportionally to Georgia’s GDP growth was given an opportunity to earn additional revenues from advertisements. Of further note is that Law of Georgia on Public Procurement is not applicable to the Public Broadcaster when it purchases tele-radio products or/and related services which arguably creates risks of corruption. In accordance to the NGOs operating in Georgia as well as the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics these amendments posed a risk with respect to the accountability and transparency of the Public Broadcaster. On top of that, media professionals believe that would be harmful for commercial TV channels, particularly regional and small televisions, since amendments put them in unequal as compared to the Public Broadcaster situation.

On 20 September 2019, the Parliament of Georgia adopted the Code on the Rights of the Child which came into effect on 1 September 2020. According to the Section 1 of Article 66 of this Code, “A broadcaster is obliged to ensure that a child is protected from the effect of information hazardous to the child. A broadcaster is also obliged to use classification criteria of broadcasting programs for the purposes of establishing the categories of these programs and place these programs into a broadcasting grid in accordance with the rules laid down in the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting”. As part of legislative changes 21 normative acts were amended, including law on broadcasting and law on electronic communications. It was banned to broadcast programs without age labels and specific airtime which “is not in line with the child’s age and hinder its development as well as the child’s upbringing into an independent person with a sense of social responsibility”.

Article 561 and 562 were added to the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting where a number of vague provisions were inserted. For instance, “Broadcasting of programs having harmful influence on the physical, intellectual and moral development as well as psychological and physical health of adolescents are prohibited; Broadcasting of programs or placing a content in a program having harmful influence on adolescents’ socialization is prohibited”, etc. In addition, Article 71 of the same law which lays down penalties, was also amended and the GNCC was authorized to fine broadcasters or suspend/revoke their license/authorization. These are precisely those vague definition and punishment leverage in the hands of the GNCC, which we discussed above, that media workers are concerned about. They argue that the law generates myriad unanswered questions: “For instance, do regulations apply to news broadcasts which often cover crime? Does it mean that broadcaster may be found as a transgressor if it covers a rally at 16:00 where confrontation, violence and crime took place? Can it be considered that famous Romeo and Juliette movie glorifies suicide and should not be aired at 22:00?” Broadcasters say that scenes when easily accessible utensil is used to inflict harm or as a murder weapon can be found in absolutely humane, multiple Oscar-winning animated movies. Therefore, the GNCC should clarify whether broadcasting Tom and Jerry or Spiderman during daytime hours will be considered as a transgression. Given all these factors, media started to have a legitimate fear that in the name of protecting the right of the child, administrative bodies would use punishment levers at its disposal against the critical of the government media.

Of note is that the controversial changes adopted by the Parliament were appealed to the Constitutional Court of Georgia. In accordance with 22 February 2023 ruling of the Constitutional Court, application was only partially satisfied and normative content of Sections 4 and 5 of Article 71 of the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting were declared unconstitutional. These passages envisaged imposing penalty to broadcasters if they live broadcasted harmful for the adolescents information/content under such circumstances when despite resorting to every possible measure of caution under respective circumstances, broadcaster could not anticipate and was not able to anticipate the possibility of such content ending up on air”.

Ultimately, there are still a number of vague and previously unanticipated regulations when it comes to intersection of rights of the child and media which can be used against the critical of the government media through the administrative body – GNCC and have a so-called chilling effect on media workers.

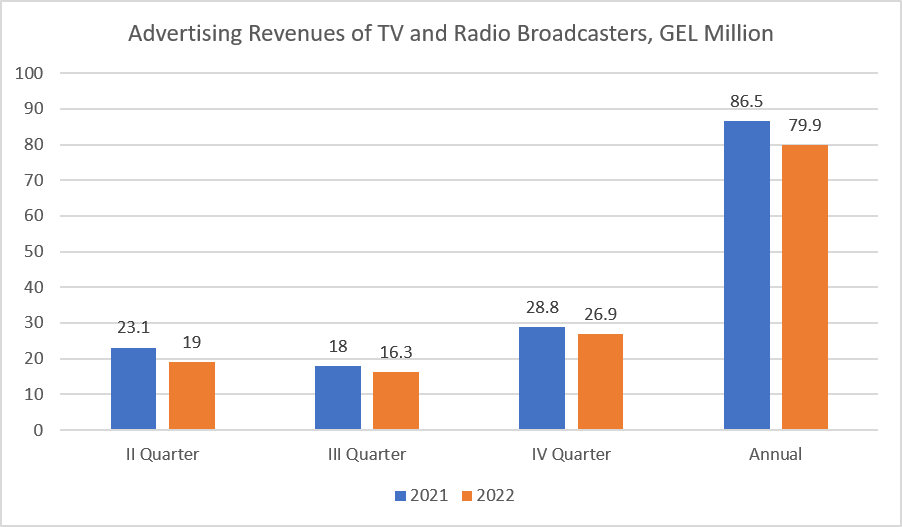

Since 1 March 2022, regulation on prohibition of gambling advertisements went into effect which drastically reduced revenues of broadcasters and made already low-income sector further vulnerable financially. According to the reports of the GNCC this regulation is the reason behind shrinking revenues of broadcasters in the last year. In particular, in the second quarter (April-June) of 2022, total commercial advertising revenues of TV and radio broadcasters amounted to GEL 19 million which was GEL 4.1 million (17.5%) less as compared to the same period of the previous year. In the third quarter (July-September) of 2022, total commercial advertising revenues of TV and radio broadcasters amounted to GEL 16.3 million which is GEL 1.7 million (9.3%) as compared to the same period of the previous year. In the fourth quarter (October-December), advertising revenues of TV and radio broadcasters reached GEL 26.9 million which was nearly GEL 1.9 million (6.7%) less as compared to the same period of the previous year.

When measured in year-over-year figures, total advertising revenues of TV and radio broadcasters in 2022 decreased by 7.6% as compared to 2021 and amounted to GEL 79.9 million. According to the GNCC data, advertising revenues earned from gambling sector in the second, third and fourth quarters of 2021 were GEL 14.3 million whereas in 2022, revenues generated from gambling advertisements effectively came down to zero.

Graph 1: Advertising Revenues of TV and Radio Broadcasters, GEL Million

Source: Georgian National Communications Commission

On 22 December 2022, a number of amendments were enacted in the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting with respect to hate speech and media self-regulation. These changes were initiated by the MPs of the ruling Georgian Dream party. Gnomon Wise published a research study on these regulations as early as when amendments were still at draft law stage. Below, we will present major findings of that study. The vaguest and simultaneously the most controversial element of the amendments is regulation of hate speech. Hate speech largely falls under a category of subjective perception or assessment and there is no international recognized or universally adopted definition among public or media industry. Regulation of hate speech is associated with huge risks, because instead of accomplishment of some benevolent objectives, we may end up with disproportionate suppression of the freedom of expression.

As a result of legislative changes, a special article (552 – prohibition of programs and advertisements, containing hate speech and calls for terrorism) was added to the “Law on Broadcasting” which prohibits “such a program or advertisement that contains information inciting violence or hatred against a person or group based on disability, ethnic, social origin, gender, sex, gender identity, nationality, race, religion or belief, sexual orientation, skin color, genetic characteristics, language, political or other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth or age, except where necessary due to the content of the program. It is also “prohibited to show such program or advertisement that contains calls for terrorism”.

According to the previous version of the Law on Broadcasting, violations with respect to hate speech (sections 2 and 3 of Article 6) were reviewed by a broadcaster’s self-regulation board and decision could not be appealed in the GNCC or court. After adopting changes on 22 December 2022, responding to such violations has become an obligation of an administrative body which is Georgian National Communications Commission (GNCC). Therefore, the issue of hate speech moved from the scope of self-regulation into a scope of regulation and the GNCC was given yet another instrument to interfere in media content. Consequently, the GNCC is authorized to impose different sanctions if it considers that a broadcaster promoted hate speech. In particular, the GNNC will give a reasonable time to the provider of audiovisual services or/and radio broadcaster to address or prevent violation. In addition, GNCC has to impose penalty charges over a broadcaster if the latter fails to take written notice into consideration. After imposition of a penalty charge for the first time, if violation continues or there is a new case of violation in the course of one year, a broadcaster will be fined with double amount or public administrative proceedings will be launched to suspend license/authorization. After being fined for the second time, amount of fine doubles again or process of suspending license/authorization is launched.

Apart from the abovementioned, a special article on “right to reply” (521) is also added to the “Law on Broadcasting”. According to that article, “any interested party whose legal interests has been damaged by the assertion of incorrect facts in a broadcaster’s program shall have a right to reply in a manner prescribed by this law.” This manner is defined in the following sections of the Article 521: “The interested party shall be entitled to demand that a broadcaster issue a correction or retraction of incorrect fact in 10 days after making a statement, including assertion of fact, with commensurate means and form when correction should be of the same length as initial statement and made approximately in the same time when the initial statement was made”. In addition, “refusal of a broadcaster to correct a wrong fact in a statement with commensurate means and forms or retract a statement can be appealed to the GNCC or a court”. This issue also creates unjustified risks of interference in freedom of expression, because here too, it is a prerogative of the GNCC to decide whether or not a specific individual’s interests has been damaged by the media. Therefore, questions are raised – how competent is the GNCC for such discussions? Or how impartial will the GNCC be when considering such disputes?

Yet another dangerous amendment, which came into effect by the end of 2022, is as follows – under previous legislation, “Legal acts of the GNCC may be appealed to a court as determined by legislation” (Article 8, Section 7). In accordance with the enacted amendments, “Court accepting the lawsuit for a review will not lead to suspension of legal act of the GNCC, except for the case, when the court decides otherwise” (Article 8, Section 7). Therefore, under a previous legislation, if the GNCC ruled against a broadcaster the latter was able to appeal to a court and once lawsuit was submitted, execution of GNCC’s ruling would be suspended until the final court ruling. However, the legislative changes increase a risk that immediate execution of the GNCC’s legal act, without substantial consideration from a court, will inflict an irreparable damage to a broadcaster.

The explanatory note of the amendments enacted in the Law on Broadcasting on 22 December 2022 says that the sole objective of the proposed amendments is to fulfil an obligation of harmonization of Georgian legislation with the EU's Audiovisual Media Services Directive 2010/13/EU which is envisaged by the EU-Georgia Association Agreement. Of note within this context, however, is that there is no unequivocal call that the Directive obliges to regulate its requirements, in this case for hate speech, in a new manner. Furthermore, in contains a passage that gives a straightforward discretion to the member states not to change existing systems if they work effectively. Of additional note is that according to Section 7 of Article 4 of the EU’s Directive, it is necessary to have a consensus between major stakeholders when making such decision which is lacking in this case. Furthermore, broadcasters and NGOs as well as professional union of the journalists (Charter of Ethics) categorically oppose such regulation of the issue.

On 6 February 2023, according to the decree of the Speaker of the Parliament of Georgia, rule of accreditation to the Parliament for mass media representatives was adopted. Although it is not a legislative change, but in its content it to a certain extent expresses the desire of the authorities to provide a comfort zone safeguarded from the critical of the government media. According to the decree, journalists who are accredited to the Parliament should observe the following rules:

- Not to disrupt parliamentary proceedings.

- Not to disrupt parliamentary proceedings.

- Not to take photographs of a MP’s or staff member’s place of work without prior permission.

- Stop an interview if an MP, staff member or guest objects.

- Not to photograph the documents, the screen of a telephone or any other electronic device belonging to an MP, a staff member or a guest in such a way that information or images on them can be seen.

- Not to treat anyone in the Parliament in a rude, sexist or discriminatory manner.

- Comply with the instructions of security staff and marshals.

- Wear accreditation badge in a conspicuous place.

- Not to pass accreditation badge on to another person.

If journalists or media outlets fail to comply these rules their parliamentary accreditations will be suspended, or revoked. Most of media organizations in Georgia, as well as the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics decried this regulation as drawing red lines for the media and attempt to restrict work of media at the Parliament. Of note within this context is that if there is a high public interest, journalists should be allowed to repeat questions to the MPs or staff members several times, despite their refusal, as well as photographing their rooms, documents or screens of their electronic devices. Under this decree, however, journalists are obligated to comply with the instructions of guards or/and marshals which ensure enforcement of the abovementioned restrictions without taking into consideration any context or high public interest.

Of further note is that decree has already been put into practice. In particular, on 6 April 2023, the Parliament suspended accreditations of several journalists and cameramen from critical of the government media outlets. It was officially stated that the reason was non-compliance with that section of the Speaker’s decree which prohibits journalists to stop interviewing an MP, staff member or guest if respondent objects. Public Defender of Georgia commented on the fact of suspending accreditations to the journalists. According to his assessment, “the rule which serves as a basis of this decision is problematic. In addition, it is not outlined in the rule how a decision to suspend accreditation can be appealed and the decision to suspend accreditation to a journalist does not contain timeframe and procedure to appeal it which is a legally necessary requirement. Notably, such attitude and decisions vis-à-vis the media workers hinder reduction of polarization in the country” …

Conclusion

The analysis of different legislative regulations with respect to the media shows that a number of them negatively affected revenues of media organizations, mostly those of TV and radio broadcasters. For Georgian media companies, most of which already face financial difficulties and with absolute majority being dependent on owners’ funding, such restrictions create risks of losing editorial independence. Apart from the financial component, as a result of different legislative amendments, capability of the GNCC – media regulatory body – to influence the media, have also broadened. In particular, the GNCC which has been a subject of reasonable questions over its impartiality and independence was given more leverage to review media products as well as content of advertising and make relevant decisions, including charging a fine to broadcasters or suspending authorization/license over such issues that prior to that fell within the scope of media self-regulation. Negative consequences of those legislative regulations have already manifested themselves and some of them pose a potential threat to media freedom and independence. Ultimately, it should be emphasized that together myriad of other factors that undermined freedom of media in Georgia, legislative changes analyzed in this paper have also made their sizable contribution in this regard.

See the attached file for the entire document with relevant sources, links and explanations.