The State of Georgian Media in the Last Decade – Progress, Stagnation and Regress

photo credit: Havana Times

This October marked 10 years since the first peaceful change of government in the history of independent Georgia. This important precedent had raised hopes that the country’s path of democratic development would have become irreversible. Together with other fields, this progress should have been reflected on media freedom which is one of the major features of a democratic country.

Prior to 2012, there have been numerous critical questions vis-à-vis the-then government in terms of media freedom. Under the United National Movement’s rule, a number of issues accumulated about limiting the freedom of speech in different forms, such as: seizing TV channels from their owners in suspicious circumstances, sending riot police to Imedi TV and suspending its broadcast in 2007, ruling party’s control over the broadcasters of nationwide coverage across Georgia, physical violence against journalists and obstruction the performance of professional duties, including arrest of photographs under the charges of treason, difficult situation in terms of ads placement as companies paying for ads were giving preference to the government media which put other companies in unequal situation as well as sharp polarization of media environment in 2011-2012, etc. Indices of multiple international organizations about Georgia proved the existence of the abovementioned problems. For instance, according to the Reporters without Borders (RSF), out of 180 countries Georgia ranked 104th in terms of media freedom in 2012 whereas according to the Freedom House it was ranked 111st of 199 countries/territorial entities.

As mentioned earlier, democratic change of government should have become an impetus for starting positive changes in terms of media freedom as well. Certainly, in the first years of the Georgian Dream’s rule there was a clear progress with respect to media freedom. However, this trend soon stopped, especially after the Georgian Dream won second term in power (with constitutional majority in the Parliament). In the third term of the Georgian Dream’s rule, media freedom in Georgia has been going downwards every year. In fact, there is a similar situation in terms of Georgia’s ranking positions in the world ratings. This is confirmed by the press freedom index of the Reporters without Borders (RSF).

Graph 1: Georgia in the RSF’s Press Freedom Index (2013-2020)

Source: Reporters without Borders (RSF)

The RSF uses seven criteria to measure media freedom. These criteria are as follows: pluralism, media independence, general media environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency of the institutions and procedures that affect the production of news and information, infrastructure that supports the production of news and information as well abuses and acts of violence against journalists. The data is collected by surveying media workers in the countries as well as the number of abuses and acts of violence against journalists in a specific country during a reporting period is also taken into account. General index of media freedom is measured based on these seven indicators and countries are given scores ranging from 0 to 100, with 100 being the best possible score and 0 the worst. According to the index, 85-100 points is considered as a good situation for the media of a specific country, 75-85 points denote satisfactory situation, 65-75 signals problematic situation whereas 45-65 points stands for difficult situation and 0-45 points is for very serious situation, respectively. The index of a specific year mostly reflects events that took place in a country during the previous year (for instance points for 2022 is a result of measuring events that occurred in 2021).

As we see on Graph 1, degree of media freedom became better in 2013-2015. In addition, Georgia’s position vis-à-vis other world countries also improved. However, this progress has slowed down in the following years. In 2022, however, there is a sharp drop both in terms of points and world ranking position. At the same time, Georgia’s media environment quality deteriorated so drastically that the country ended up in a group of countries which are considered to have a very serious situation in terms of media freedom (0-45 points).

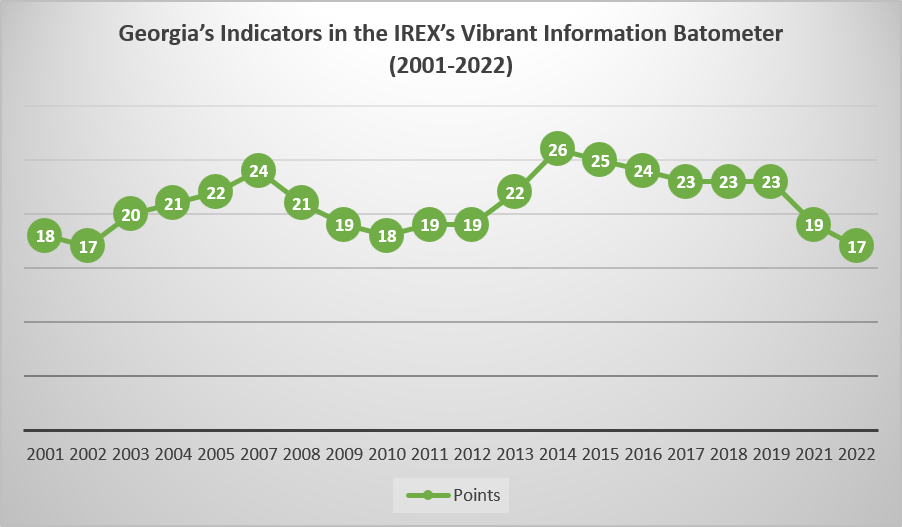

The index of the International Research and Exchanges Board also shows the similar trend. It is noteworthy that before 2021 IREX also published Media Sustainability Index which was replaced in 2021 by the Vibrant Information Barometer (VIBE). However, data of the previous years was adjusted in a way to make comparison in time prism possible.

Graph 2: Georgia’s Indicators in the IREX’s Vibrant Information Barometer (2001-2022)

Source: International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX)

Measurements of Vibrant Information Barometer are based on four main principles: 1. Information quality, 2. Multiple channels of information, 3. Information consumption and engagement, 4. Transformative actions. In turn, these principles are further divided into 20 indicators and incorporate all those important aspects needed for free and smooth functioning of the media. The lowest score of this index is zero whereas the highest is 40. A media environment within the range of 31-40 points is considered as highly vibrant which means the system is successful whereas high-quality and fact-based information is widely available. Somewhat vibrant stable media information is within the margins of 21-30 points although some shortcomings persist. The countries which garner 11-20 points are assessed as having Slightly Vibrant, weaker information system and 0-10 points are given to such information environment which is Not at all Vibrant and remains moribund. Georgia is included in the category of countries with slightly vibrant systems. Prior to 2021, Georgia was meeting criteria of somewhat vibrant system’s criteria which is one step above and is another illustration of the last year’s negative trends. Similar to the RSF index, VIBE’s index position also reflects events that took place in the previous year (for instance points for 2022 is based on the assessment of 2021 events).

This index, provided by the IREX, also indicates improvement in media freedom during 2013-2015, followed by subsequent stagnation and drastically negative outcomes of 2021-2022. Below we will discuss what caused such a decline in the past years and offer a detailed overview of the state of media from 2012 until the present day as well as those major positive/negative events that unfolded over the course of this decade.

Important Facts of the Last Decade Affecting Georgia’s Media Environment

By the end of 2012, merely two weeks after the 1 October Parliamentary Elections, TV Imedi which after infamous events of 2007 and death of Badri Patarkatsishvili (in suspicious circumstances) ended up in the hands of Mr. Patarkatsishvili’s relative Joseph Kay, was restored to its initial owners, Patarkatsishvili family under the deal between the previous and current owners. Prior to this event, Imedi was controlled by the people affiliated with the former government and pursued markedly pro-government editorial policy.

2013 – As opposed to the previous years, 2013 was a particularly outstanding period in terms of improvement of media freedom. The government’s control over the broadcasting media became weaker and general media environment became less polarized. In addition, amendments to the Law on Broadcasting which made funding for the Channel One of the Public Broadcaster as well as Adjara TV more transparent was lauded as an important step forward. The rule of staffing of the Public Broadcaster’s Board of Trustees was also improved, aimed to increase the degree of independence of those media entities. Amendments to the Election Code of Georgia and ensuring guaranteed presence of media within the polling stations was another important occurrence of 2013. In the same year, in line with the Prime Minister Ivanishvili’s decree, regulations on providing public information were also modified and government agencies were instructed to publish documents proactively on their websites and officially admit electronically submitted requests for information. “The international media monitors concluded during 2013 Presidential Elections that influence of political parties and figures on two major private broadcasters – Rustavi 2 and Imedi – was no longer discernible and currently these companies were more focused on production of competitive editorial materials”. The Channel Nine, owned by Bidzina Ivanishvili, was closed down in 2013 and its frequency was given to the GDS, entertaining TV channel owned by Bera Ivanishvili.

Together with positive changes, there were also several controversial events in 2013. In particular, one month before the Presidential Elections, Acting Director of the Public Broadcaster cancelled two political talk-shows. The anchors of those talk-shows – Eka Kvesitadze and Davit Paitchadze – were affiliated with the United National Movement and therefore this decision was considered to be politically motivated. Yet another important occurrence of 2013 was leaking of footage showing private life of TV Obiektivi’s journalist through the internet. The journalist who featured in that footage blamed the high-ranking public officials in fabrication and dissemination of the footage, and as a result, the first Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, Gela Khvedelidze, was removed from his position and detained under the charges of infringement of right to respect private life, although later he was released on bail. In 2013, both the Georgian Dream and United National Movement sought to gain influence over the Public Broadcaster which led to the crisis of governance there.

2014 – After nearly two years since the change of the government and less than one year since the Presidential Elections, Georgian media started to tremble again in 2014. Despite hopes of the media workers, improvements in the field of media were stalled, although there was no sharp deterioration of situation either. At the same time, according to the assessments of the media professionals and scholars, quality of journalist production has improved as compared to the previous years. Of note is that it was 2014 when certain positive steps were taken towards moving Georgia onto digital broadcasting with Government of Georgia adopting Digital Switchover Strategy and recommendations on 7 February 2014.

At the initiative of the Government of Georgia, a number of important legislative changes aimed at improvement of media environment was implemented in 2014, albeit without practical results. For instance, the amendments kept clandestine surveillance practice in place and relevant authorities kept right to access tele-communication networks. In addition, political influence on media was still problematic. Furthermore, implementation of the rule of election Public Broadcaster’s Board of Trustees was hindered, possibly indicating political motives. At the end of the year, 20 journalists left private TV channel Meastro, including Nino Zhizhilashvili, the head of news section and anchor of main analytical talk-show. This fact illustrated changes in TV Maestro’s editorial policy and interference in its independence.

On 31 October 2014, the Parliament of Georgia adopted the law on regulating social advertising. In accordance with the amendments, private broadcasters became obliged to place 90 seconds long social advertisements for free in every three hours. However, media workers opined that with these changes, Georgian National Communications Commission (GNCC) was given excessive control over the broadcasters as well and definition of a social advertisement was also quite vague. These and other legislative regulations posed a threat to the stability of ads-generated income for the broadcasters.

2015 – One year prior to the important Parliamentary Elections, tremors in the Georgian media became more intense. This year marked launching a court case against Rustavi 2 – critical of the government TV channel – which sparked doubts about the government’s interference in the media. The former owner of the TV channel, Kibar Khalvashvi, stated that in 2006 the-then Government of Georgia forced him to relinquish rights on the company. Of note is that Kibar Khalvashi also became owner of shares of Rustavi 2 in dubious circumstances. The Georgian Dream government denied any links with this dispute and referred to it as a “dispute between two private companies”. However, despite legal arguments provided by this or that party, dispute over Rustavi 2 which launched in 2015 put a huge question mark to the stable advancement of media freedom in the country. This has become an extremely important issue after court ruled that temporary manager should be appointed in Rustavi 2. The dispute about ownership of Rustavi 2 continued in the subsequent years and different court chambers, all the way through to the European Court of Human Rights. Therefore, we will raise this issue many times in the following pages.

Despite the abovementioned fact, Georgia’s media environment in 2015 was still one of the freest in the region. However, the practical implementation of legally guaranteed mechanisms of freedom of speech still remained a problem. The digital switchover process in 2015 was rather effectively carried out, bar certain shortcomings. Eventually, digital switchover increased Georgian public’s availability of information.

In 2015, amendments were made to the Law on Broadcasting to define precise intervals of placement of ads or tele-shopping. As claimed by the Government of Georgia, adoption of those amendments was precipitated by the European Union’s directive. However, it turned out that enforcement of those amendments in 2015 was not required by the European Union’s directive as well as it did not demand such tight regulations which was envisaged by the amendments offered by the authorities. What is more, these amendments affected already scarce ads-generated incomes of the broadcasters which eventually had a negative impact on media’s financial independence. It should also be added vis-à-vis 2015 that the anti-Western propaganda started to become increasingly vocal in the Georgian media environment.

2016 – During the Parliamentary Elections year, together with rising political tensions in the country, media environment also became more polarized. In addition, many challenges from the previous years persisted and some of them even worsened, as independence of certain media agencies was further undermined by suspicious contacts with the authorities. In addition, some of the mouthpiece of the Kremlin propaganda, such as TV Obiektivi, became more active and the political party spawned from that TV channel, named as the Alliance of Patriots of Georgia, passed electoral threshold to gain seats in the new parliament. Finally, situation worsened in terms of diversity of news sources and media management.

The high-profile case of Rustavi 2 continued over the course of 2016 is different court instances. In addition, ownership dispute was also launched with respect to Maestro TV channel. Since 2016, TV Maestro was handed over to new managers and control package of the company was acquired by Giorgi Gachechiladze, known as “Utsnobi”.

In 2016, during the pre-election period, some in the public blamed GNCC for employing a “selective approach” vis-à-vis the broadcasters. In particular, on the ground of violation of rules of coverage of election campaign’s different aspects, the administrative body issued fines against critical of the authorities Rustavi 2 and Tabula whereas used only warning in case of Public Broadcaster, GDS and TV Obiektivi.

In 2016, several public figures, including critical of the government journalist Inga Grigolia, were threatened with the publication of footage of her personal life. That year, particularly during election day, there were facts of obstruction of journalistic works when journalists of GDS, Rustavi 2 and Iberia were abused and their cameras were destroyed. According to the assessment of the media workers and scholars, in 2016, media became even more polarized as compared to the previous years [under the Georgian Dream’s rule].

2017 was a notorious year because of a fact that turned out to be equally shocking for the Georgian media and others. On 29 May 2017, Azerbaijani journalist and civic activist Afghan Mukhtarli disappeared in one of Tbilisi’s central avenues. Later, it was reported that the journalist had been detained in Azerbaijan. As stated by Afghan Mukhtarli’s lawyer, the journalist was detained near his apartment in Tbilisi, had his hands tied and was physically abused by some unknown persons. As per Mukhtarli’s assumption, the abductors were officers of the Georgian special services. According to the lawyer, his client had a bag put over his head and was driven for two hours in unknown directions, changing the car twice in the process. In the third car, he was already surrounded by Azerbaijani-speaking individuals. This fact prompted swift and harsh criticism across the international community and Georgia’s image, which was previously considered a shelter for Azerbaijani dissidents and a safe country for journalists, was severely tarnished.

In 2017 problems with respect to the financial independence and sustainability of media outlets still persisted. In addition, the trend of polarization manifested in 2016 continued to intensify, whereas Public Broadcaster and GNCC, which are funded by the state budget to serve public interests, continued to attract doubts about being loyal to the government. In January 2017, Vasil Maghlaperidze, who used to work in the management team of GDS and Channel Nine, owned by the Ivanishvili family, became Director of the Channel One of the Public Broadcaster. In June, Radio Freedom’s two broadcasts, “Red Zone” and “Interview”, which ran for years were shut down on Channel One of the Public Broadcaster. Afterwards, for some time, these broadcasts were aired at Adjara TV. In addition, Channel one of the Public Broadcaster, hired former and current employees of GDS who previously were used to be anchors at the talk show 2030 founded by Bidzina Ivanishvili. Of note is that from January 2017, GDS joined media holding TeleImedi, which also consists of other pro-government TV channels – Imedi and Maestro. The court dispute and uncertainty over the future of Rustavi 2 still persisted.

In October 2017, GNCC unveiled draft amendments to the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting which envisaged the obligation of broadcasters to verify pre-election opinion poll results. Given the GNCC’s authority to fine a broadcaster for this or that violation, media workers perceived this initiative as an attempt to create one additional instrument of control over the critical media. Of further note is that the above-mentioned law still has not come into force.

2018 – In view of the autumn presidential elections and other political events, that year was rather tense for the media as well. In accordance with the assessment of media workers and monitors, there were more assaults against journalists, including physical assaults, as compared to the previous years. Journalists became victims of different types of attacks by far-right actors who have openly pro-Russian stances. One such fact was the gathering far-right groups near Rustavi 2 when they verbally abused journalist Giorgi Gabunia because he mentioned Christ when making a joke about Bidzina Ivanishvili. In addition, the rhetoric of the Government of Georgia vis-à-vis Rustavi 2 became more hostile, as the high-ranking public figures blamed the TV channels for distorting reality and promoting false information. In addition, a dispute over the ownership of Rustavi 2 continued but this time as part of the European Court of Human Rights legal process.

In 2018 there were attempts to impose tighter regulations against freedom of speech and expression. One group of the MPs initiated bringing criminal responsibility for “offending religious sentiments”. In addition, GNCC’s draft law on hate speech was also initiated to move the latter from self-regulation to a regulated framework. The leverage of enforcement of this regulation was to be handed over to the GNCC. These initiatives have not been transformed into laws. However, in February 2018, amendments to the Law on Broadcasting were put into force, and according to those amendments, limits on commercial advertising and sponsorship on air on Public Broadcaster were decreased to a minimum. Therefore, the Public Broadcaster, which already gets funded by the state budget and has its finances growing proportionally to the GDP, was allowed to earn additional ad-generated revenues. According to the assessment of some Georgian-based NGOs, these amendments posed risks to the accountability and transparency of the Public Broadcaster and contributed to higher risks of corruption. In addition, media workers claimed that it hurt commercial TV channels, in particular regional smaller channels, as amendments put them into unequal positions vis-à-vis the Public Broadcaster.

In 2018, Georgian media was afflicted by some persisting problems, which even deepened in some aspects and are as follows: journalists’ access to public information, financial and infrastructural problems of the media outlets, professional coverage of the issues, etc.

2019 – Similar to the previous year, there were massive political tensions and polarization in 2019 as well, which was duly reflected on the media. The political turbulence reached its peak on 19 June 2019 when people rallied after the Russian State Duma member Sergey Gavrilov, appeared in the Parliament of Georgia (Gavrilov was invited to the Parliament as part of a session of the inter-parliamentary assembly on orthodoxy). During the night of 20 June when some of the protesters tried to enter the premises of Parliament, riot police started to disperse the rally with special equipment. As a result of these events, over 30 journalists were injured, including some who were hit by rubber bullets. Two journalists sought immediate surgical intervention. Johann Bihr, the head of RSF’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk, said that the “media have been subjected to unacceptable violence”. Although there were multiple facts of injuring journalists during the crackdown, none of them was able to obtain the status of victim in 2019, and some appealed to the European Court of Human Rights in this regard.

2019 was decisive for the years-long dispute over the ownership of Rustavi 2. On 18 July 2019, in line with the European Court of Human Rights ruling, Kibar Khalvashi became the owner. After this ruling, international organizations working in the field of media called on the owner to ensure editorial independence and refrain from firing journalists. Nevertheless, Kibar Khalvashi ousted the Director of Rustavi 2 Nika Gvaramia and appointed Paata Salia, his lawyer, in his stead. After changes in Rustavi 2 ownership, the new General Director fired some of the leading journalists. This decision sparked protests among many journalists, and eventually, over 60 journalists left the TV channel. Some of the former journalists of Rustavi 2 started to work either for Mtavari Arkhi, a new TV channel founded by the former Director General Nika Gvaramia or TV Formula, also a newly established broadcaster. Therefore, despite all the legal practicalities of the case, eventually, an editorial policy of a TV channel critical of the government changed in 2019.

In 2019, Prosecutor’s Office pressed charges against the former Director of Rustavi 2 and founder of Mtavari Arkhi, Nika Gvaramia, on the ground of “abusing administrative and representative authority”.

2020 – As for every other field, the pandemic 2020 turned out to be particularly hard for journalists as well. In view of the global economic downturn, including an economic decline in Georgia, the financial sustainability of the Georgian media was also dealt a heavy blow. Against the backdrop of rapidly surging COVID-19, online disinformation and myths posed a particular problem. In addition, anti-Western propaganda continued to be an important challenge. It was not uncommon when journalists received aggression instead of answers from the government and health authorities for their critical questions when covering COVID-19. At the same time, access to public information was also limited amid the pandemic. Furthermore, several journalists were physically assaulted before and after the 2020 Parliamentary elections, and the government was unable to prevent it.

In 2020, the government started investigations against journalists when journalists of TV Mtavari were accused in “sabotage”, spreading disinformation and smearing the government. In addition, media workers noted that criminal proceedings launched since 2019 against Zuka Gumbaridze (Director of TV Formula) and Nika Gvaramia (Director of “Mtavari Arkhi”) were manipulatively using the law, although in fact, the real reason was critical positions of these broadcasters. Moreover, media workers and monitors believed that there were discernible attempts to silence critical media in the actions of the government and pro-government GNCC. In addition, the government’s efforts to marginalize groups critical of the authorities (media, NGOs, etc.) became even more crystalized.

Dramatic events unfolded in Public Broadcaster’s Adjara TV when Deputy Director Natia Zoidze announced her resignation. She noted that “resignation did not reflect her will” and was an outcome of a political process. Previously, in December 2019, she blamed the new Director of Adjara TV, Giorgi Kokhreidze, for pressuring to change editorial policy. Adjara Public Broadcaster’s Alternative Trade Unions commented on Natia Zoidze’s resignation: “Natia Zoidze leaving her job is nothing but a fact of interference in editorial independence. This is no longer an attempt. This is an outcome and first and foremost, Broadcaster’s Board of Advisors and Director shall bear full responsibility. We, employees of the Broadcaster, will continue to fight to preserve independence because authority rests in the hands of people to whom values and mission of the broadcaster are unacceptable concepts”. In the spring of 2020, several more journalists were fired from Adjara TV, and the reason was their public (Facebook publication) criticism against the TV channel’s management.

2021 – The previous year was extremely difficult for the Georgian media. On 5 July 2021, the pro-Russian mobs, engaging in advance-prepared violence, obstructed holding March of Dignity at Tbilisi’s Rustaveli Avenue. In addition, they physically assaulted over 50 journalists who were gathered to report the events. Given the number of injured journalists and dynamic of events, it is possible to say that leaders who orchestrated the violence had specifically targeted media workers. The police could not prevent this violence, authorities did not mobilize sufficient forces and as a result it became impossible to avert the savagery. In a few days, cameraman (TV Pirveli) Lekso Lashkarava who was beaten during 5-6 July events, has died. The organizers of the violence who vocally called for people to commit such actions in the run-up to 5 July have not yet been brought to justice. Media workers and monitors are in full agreement that 5-6 July events sharply worsened Georgia’s media environment and made journalistic profession even more dangerous. In addition, Media Advocacy Coalition, compiled 37 facts of verbal and physical assault against journalists and activists in 2021. Meanwhile, in light of the Municipal Elections held in the autumn of 2021, attacks against journalists continued unabated. Of note is that at the beginning of 2021, drunk people attacked TV Formula anchor Vakho Sanaia and his family. The offenders were released from jail in six months.

In September 2021, it was reported in the media that the State Security Service of Georgia (SSS) had carried out illegal wiretapping of politicians, clergy and publicly active people in general, including journalists. Five journalists confirmed that reports leaked in the media (the so-called “denunciation”) in fact reflected their private communications, meaning they had been targets of illegal wiretapping.

Media workers and scholars also expressed concerns that the government’s disinformation accusations as well as hate speech against the critical media became harsher in 2021. In addition, control over the release of public information tightened, and polarization in the media environment made it even more acute.

In 2021, anchor of the Public Broadcaster’s “Week Interview”, Irakli Absandze, was fired from his position. It was reported that the official reason for Absandze’s dismissal was his violation of Public Broadcaster’s code of conduct. However, as stated by the journalist himself, he was fired for his critical statements against the government.

2022 – Since 1 March 2022, ban on gambling ads went into force which sharply reduced revenues of the broadcasters and made already less profitable sector even more financially vulnerable. The statement of the GNCC reads that “total commercial ads revenues of the TV and radio broadcasters in the second quarter of 2022 was GEL 19 million which is GEL 4.1 million or 17.5% less as compared to the same period of the previous year. Decrease in ads revenues is attributable to the new regulation on gambling ads… Of note is that prior to the enforcement of the regulation, gambling organizer companies were among large financial contributors of the broadcasters. In the second quarter of 2021, TV channels and radios earned over GEL 4.6 million ads revenues from gambling companies.”

On 7 September 2022, draft amendments to the Law of Georgia on Broadcasting were submitted to the Parliament of Georgia. The authors of the draft law are MPs of the ruling Georgian Dream party. These amendments are almost identical of the changes proposed by the GNCC in 2018, which were discussed above. One of the vaguest and at the same time, perhaps the most controversial part of the proposed amendments is the regulation of hate speech. This initiative contains a risk that regulations will be abused by incumbents or any future governments vis-a-vis the media. At the time of writing (31.10.2022), the Parliament of Georgia adopted the draft law on the first hearing.

On 16 May 2022, the Director of the Mtavari Arkhi, Nika Gvaramia, was arrested. As mentioned previously, the investigation against him started as early as in 2019, and the case is about Gvaramia’s role as Director of the Rustavi 2. Public Defender of Georgia, as well as local and international organizations, highlighted politically motivated grounds of this case.

Conclusion

This paper offers an overview of the state of Georgian media over the last decade, that is, since one of the most important milestones in Georgian history - change of government through elections – until the present day. Analysis of myriad facts and sources illustrated that the country failed to make use of good starting positions in 2012 vis-à-vis democracy in general and media freedom in particular. There was political will coupled with some practical attempts in the first years under the new government to improve the state of media, although these trends came to nought with the ending of the first term of the Georgian Dream’s tenure. During the past few years, in the third term of the Georgian Dream’s rule, media freedom in Georgia has been declining annually. This is confirmed by facts discussed in this paper as well as the constantly deteriorating positions of Georgia in various international indices measuring media freedom. On top of that, recently, the Government of Georgia’s aggressive and propagandistic rhetoric against media has been increasingly visible and broader, which is one of the specific features of the non-democratic regimes in the modern world.

References:

Absandze, T. (29 December 2017). “Commercial” Public Broadcaster. FactCheck Georgia. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3U71k3C (31.10.2022).

Adjara Public Broadcaster (3 February 2020). We, employees of the broadcaster, continue to fight for preserving independence – Alternative Trade Unions. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3SLtvnC (31.10.2022).

Channel One. Vasil Maghlaperidze – Resume. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3NjdZyl (31.10.2022).

Chimakadze, N (2018). How the media environment changed in Georgia over the last ten years? Media Checker. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3TPExti (31.10.2022).

Civil.ge, (1 June, 2013). Parliament Confirms Amendments to Law on Broadcasting. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3SRD1FG (31.10.2022).

Civil.ge, (9 August, 2019). Prosecution brings charges against Nika Gvaramia. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3UtDn6X (31.10.2022).

Giunashvili, G. (9 September, 2016). Former employees of “Mastro” to receive compensations from the company. Netgazeti. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Uatgn7 (31.10.2022).

GNCC (2016). Annual Report 2016. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Njc8cR (31.10.2022).

GNCC (9 August 2022). Ads Revenues of TV Channels and Radios in the Second Quarter of 2022 was GEL 19 Million. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Nke44P (31.10.2022).

GNCC. (25 March, 2015). What should we know about digital broadcasting? Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sI4Ohp (31.10.2022).

Gugulashvili, M. (11 August 2021). Why Guram Absandze was fired from Channel One. Media Checker. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3gMHsUW (31.10.2022).

Gugulashvili, M. (20 June 2020). Uninvestigated cases of journalists injured on 20 June and lawsuits in Strasbourg. Media Checker. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3FxX890 (31.10.2022).

Gvadzabia, M. (16 May 2022). Why was Gvaramia arrested. Netgazeti. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sKy5YJ (31.10.2022).

Human Rights Centre (2014). Georgian Media in Transitional Period (2012-2014). Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3zuK3JY (31.10.2022).

Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI). Secret Surveillance in Georgia: 2015-2016. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3NnkMXI (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2013). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Nng5NA (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2014). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sIeiZW (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2015). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3TQ7MMx (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2016). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Nj0RsZ (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2017). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3No4T3b (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2018). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sN3daa (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2019). Media Sustainability Index. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3zT3Bb9 (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2021). Vibrant Information Barometer. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3NjX9PQ (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). (2022). Vibrant Information Barometer. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3NjeaJX (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). Media Sustainability Index (MSI). Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3NpiaJ2 (31.10.2022).

International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). Vibrant Information Barometer. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3FuG0AS (31.10.2022).

Jikia, T. (13 February, 2015). Davit Bakradze says that amendments to the Law on Advertising are not an immediate necessity. FactCheck Georgia. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3D8nZ8Z (31.10.2022).

Ketsbaia, T. (6 June 2017). How is it possible to disappear in Tbilisi and find yourself in Azerbaijan? FactCheck Georgia. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3TOkvzf (31.10.2022).

Kevanishvili, E. (6 November 2015). Temporary Management in Rustavi 2. Radio Freedom. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3WfxPyu (31.10.2022).

Kutidze, D. (2020). Challenges for the Georgian Media – Missed Opportunity for an Irreversible Progress. Research Institute Gnomon Wise. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3DLOdzj (31.10.2022).

Kutidze, D. (2021). The Government of Georgia’s Aggressive and Propaganda Rhetoric Against Media – Proven Method of the Authoritarians to Discredit the Journalists. Research Institute Gnomon Wise. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sKtypa (31.10.2022).

Kutidze, D., Gurgenashvili, I. (2020). “Limiting Freedom of Expression in the Name of Fighting Hate Speech?!” Research Institute Gnomon Wise. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Wg0Z0h (31.10.2022).

Kutidze, D., Gurgenashvili, I. (2022). Amendments to the Law on Broadcasting – Threat of Censorship Through Biased Interpretation of the European Union’s Directive. Research Institute Gnomon Wise. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Ub37Vh (31.10.2022).

Media Development Foundation (MDF), (2016). Anti-Western Propaganda. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3SPAewP (31.10.2022).

Meparishvili, M. (13 June 2017). “Red Zone” and Salome Asatiani’s “Interview” will no longer be aired on Public Broadcaster. Netgazeti. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3SRHo3y (31.10.2022).

Netgazeti (16 October, 2013). ‘Imedi’ returns to Patarkatsishvili family. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sLSwEG (31.10.2022).

Pertaia, L. (24 July 2019). Everything you need to know about the case of Rustavi 2. Netgazeti. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3zwRwbn (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (1 October, 2020). At least five journalists attacked while covering Georgia’s election campaign. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3SLEVrD (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (12 July, 2021). Georgia: Suspicious death of a journalist attacked six days earlier by homophobic lynch mob. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sJa6Jl (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (22 June, 2019). Many journalists injured during protest outside Georgian parliament. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3gWHAS7 (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (24 July, 2019). Media pluralism must be preserved in Georgia, RSF says. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3Wl1YMX (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (24 May, 2022). Georgia: RSF seeks review of opposition TV chief’s conviction, jail sentence. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3SWyVfA (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (24 September, 2021). RSF calls for rapid results from enquiry after journalists spied on in Georgia. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sGNf1f (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (31 May 2017). Azerbaijani journalist abducted in Georgia, taken to Azerbaijan. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3zze23d (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (5 February, 2020). Georgian TV channel’s deputy director resigns under pressure. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3sM4VZg (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), (7 July, 2021). Attacks on 53 journalists is a major setback for press freedom in Georgia, RSF says. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3DOUQ4e (31.10.2022).

Reporters Without Borders (RSF). Media Freedom Index Methodology. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3NkRJ70 (31.10.2022).

Social Justice Centre (2020). One Year Since 20-21 June Events. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3TXnGVx (31.10.2022).

Social Justice Centre, (2021). Legal Assessment of 5-6 July Events – Initial Analysis. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3DOoSVN (31.10.2022).

Tabula, (11 May, 2020). Rekhviashvili: People for Facebook publications are prosecured in North Korea, Russia and Adjara TV. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3fiH1BE (31.10.2022).

Transparency International Georgia (2014). Introducing digital terrestrial TV in Georgia – everything you need to know about government’s switchover strategy. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3zttiOY (31.10.2022).

Transparency International Georgia, (2020). Georgian Media Environment in 2016-2020. Accessible at: https://bit.ly/3DN8Qv9 (31.10.2022).

See the attached file for the entire document with relevant links and explanations.